Desert Safari

Safari tours offer visitors the chance to escape the crowded sites of Cairo and the Nile Valley and experience the peace and tranquillity of the empty desert and its green Oasis.

The popular image of the desert is of endless seas of sand. However, the vast expanse of rock in the interior of the desert is considered a part of the desert.

Apart from the new Bedouin desert-dwellers, the area is uninhabited.

Deserts provide the perfect atmosphere for some really interesting activities and great adventures. Fayoum is the closest desert area to Cairo and provides a wealth of history mixed with desert adventure.

You’ll have a chance to feel the adrenaline rush while driving on the crest of a sand dune or sliding down the dune, or sand surfing. There will also be chances to see indigenous wildlife.

You’ll meet Bedouin people and see their interaction with the environment, and enjoy the desert way locals would around a campfire at night. You can experience the clearest night skies as you drink traditional Bedouin tea and enjoy a traditional dinner slow-cooked in the heat under the sand.

A popular desert safari activity is sandboarding. Sandboarding is a slightly more forgiving version of snowboarding but gives a similar adrenaline rush.

Real Fayoum

Enjoy our bundles of Fayoum tours on our Real Fayoum website, You can check our Website here.

Adventure and desert safari tours

- Bahariya OasisSituated in a 100km by 40km (62 by 25 miles) depression and completely surrounded by high black escarpments, Bahariya is a natural treasure of Egypt and well worth visiting, the landscape here is surreal and constantly changing. The valley floor is covered with lush groves of date palms, olives, ancient springs, and wells. Bahariya was the hub of the great caravan tracks between the Nile Valley and Libya, it was an important center for agriculture and wine production, as well as a source of minerals since Pharaonic times. Now, it is a famous starting point for many desert safari adventures in the vast Western Egyptian desert, especially the famous White Desert and The Black Desert.

What to see:

The Temple of Alexander is the only temple thought to be built by Alexander in the Oasis of Egypt. Today, little of the temple remains intact, most of it has become ruins due to the surrounding desert wearing it away. Bahariya Heritage Museum shows objects documenting the various aspects of life in the oasis and local customs and traditions. The 4 Chapels of Ainel-Muftella were part of a temple complex built during the reign of the Pharaoh Amasis, 26th Dynasty (569-526 BC). Its walls were decorated with bas reliefs that are in a fine state of preservation. The Golden Mummies Museum displays an amazing collection of Roman mummies found in the famous Golden Mummies Valley, which is the most spectacular discovery in 1996 since Howard Carter opened the tomb of Tutankhamun, where hundreds of Roman mummies covered in gold were found by accident in the middle of nowhere in the desert. The Bawiti village is considered the capital of Bahariya and is very picturesque, a stereotypical image of a desert village – palm groves surrounding clusters of mud-brick houses. Bawiti has two well-preserved, rock-cut, richly decorated tombs dating back to the 26th dynasty (664-525 BC). They are the rock-cut Tomb of Zed-Amun-ef-ankh and the Tomb of his son Bannentiu.The ruins of the World War II fortress that the British controlled area on the top of The English Mountain. It offers the best view over the oasis, especially at the sunset.

- Fayoum OasisThe sites visited in Fayoum depend on the number of days in your tour, see your chosen itinerary for which they will be included. You can visit just for the day on a Real Egypt day tour, camp overnight in the surrounding desert or spend a night in an eco- hotel and spread your visit over two or three days of adventure. FAYOUM is one of Egypt’s seven beautiful oasis. It is the closest oasis to Cairo, about two hours drive, making it very accessible if Cairo is your base for travelling. Fayoum offers a diversity of beautiful natural landscapes and geological formations including lakes, sand dunes, valleys, and waterfalls. It has a rich and interesting range of flora and fauna. This 692 square miles (1114 km2) is a depression that was a lush paradise during prehistoric times. Qarun Lake covers 254 square km (98 square miles) and has a variety of migrating and resident birds. Fayoum also has beautiful villages and a flourishing crafts and artistic community. Fayoum has many places of historical interest and is a UNESCO heritage site. Fayoum was favoured during the Middle Kingdom (1991–1790 BC), and 12th Dynasty kings Senwosret II and Amenemhat III built pyramids in the area. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, it was a popular getaway for the Egyptian royal family and Cairo elite. Fayoum includes two areas declared as protected by the Egyptian Government: Lake Qarun and Wadi Rayan National Parks. It is divided into six administrative centers of which the chief towns are Madinat al-Fayoum, Tamiya, Sinnuris, Ibshawai, Yusuf al Siddiq and Itsa, comprising approximately 157 villages and 1,565 hamlets and with a population of more than 3 million inhabitants. Fayoum is a vast depression that at its lowest level contains a great lake called Birkat Qarun (Lake Qaroun). This depression receives water from a branch of the Nile that was made into a canal in ancient times, now called Bahr Joussef. This splits up into a dense network of secondary canals. Fayoum is usually referred to as an oasis, but it differs from other oases as it receives water directly from the Nile. In the 1960s, Egyptian authorities created three lakes in the Wadi Rayan depression, southwest of Lake Qarun, to hold excess water from agricultural drainage. This was intended to be the first step in an ambitious land-reclamation project, though not everything went to plan when the water started to become increasingly brackish. On the positive side, these man-made lakes became particularly conducive to large colonies of birds, leading to the entire depression being administered as a national park. Name and Etymology Fayoum had several different names through the ages. In ancient Egypt in the Old Kingdom it was called “Shedet” in reference to the lake, and in the Middle Kingdom it was called “Ta-She” meaning (The land of the Lake). The modern name of the city comes from Coptic “Pa-Ym” – payom – meaning the Sea or the Lake, which in turn comes from late Egyptian “Pa Ym” of the same meaning, a reference to the nearby Lake Moeris. It was called Al Fayoum after the Arab conquest of Egypt – land of the lake. Climate: Fayoum enjoys a hot dry climate with rare rain in the Winter, the temperature ranging in the Winter between highs of 11 to 17 and lows of 4 to 10 degrees in January, and the average annual rainfall is around 17 mm. “Cool are the dawns; tall are the trees; many are the fruits; little are the rains”, el Nabulsi wrote 750 years ago. Fayoum is best visited using a 4×4 car as the road is uneven and you have to navigate desert sands to reach attractions. Fayoum is an all year round attraction but to enjoy the best weather and your time more we advise: BEST TIME TO VISIT

- Bird watching: during Winter to observe the bird migration.

- Hiking, trekking and sand-boarding: October through May, as the weather can be very hot in the desert during Summer.

- Chilling out near the lakes: all year round.

- Fishing: September through July.

- Sandboarding: all year round. The most famous sand boarding spot is Qoussour El-Arab.

- Qarun lakeDiscover authentic desert adventure at Lake Qarun; a popular weekend spot for people from Cairo who want to cool down and unwind. The lake edge has cafes and wedding pavilions. It is not a popular swimming spot, more appreciated just for the views. You can also rent a rowing boat here. Thousands of migratory birds rest here during their Winter migration South, including large numbers of flamingos. Before the 12th Dynasty reigns of Sesostris III and his son Amenemhat III, the area now known as Al Fayoum was covered by Lake Qarun. These pharaohs dug a series of canals linking Qarun to the Nile and drained much of the lake to reclaim land. Over recent centuries the lake has regained some of its former grandeur due to the diversion of the Nile to create more agricultural land, and it now stretches for 42km. However, because it is 45m below sea level the water has suffered from increasing salinity. Wildlife has adapted to form a large ecosystem; there are many varieties of birds, most evident in Autumn, including a large colony of flamingos, grey herons, spoonbills and many duck species.

- Wadi El RayanWadi El Rayan is the home of the only waterfalls in Egypt, making it a popular Summer resort for Egyptians and a paradise for bird watchers, an authentic desert adventure. Two lakes in the middle of the desert, man-made lakes created by agricultural run-off water from Fayoum oasis, were joined together by a channel and a waterfall. This is a beautiful landscape, a wide area of desert with multiple sand dunes, home to a diversity of bird species and to several animals rare or close to extinction such as Dorcas gazelles, Ruppell’s sand fox, and Fennec fox. You can take a wooden rowboat out to the middle of the lake before coming back to the falls, around an hour long trip. Wadi El Rayan is also a major nesting ground for both endemic and migrating birds, so be sure to have your camera ready. Gebel el Medawara in Wadi El Rayan provides a great view overlooking Rayan Valley and lakes.

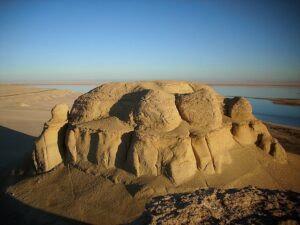

- Whale ValleyDiscover authentic desert adventure at one of this Unesco World Heritage Site; a home to the earliest prehistoric whale fossils discovered. More than 400 basilosaurus and dorodontus (both water predators) skeletons found here are around 40 million years old. They show clearly the evolution of land-based mammals into sea-going ones, as they have vestigial front and back legs. The sands are also studded with the remains of manatees and big bony fish which look out of place in the vast desert. In addition to fossils, the valley is rich in different types of rock formations weathered by water and air to create interesting patterns and shapes. The Whales Valley is also a beautiful campsite, a good escape place with toilets and camping facilities. Wadi Al Hittan Fossil and Climate Change Museum. The circular one-room museum provides a good explanation of the geological history and nature of the area, with a series of information boards and fossil displays surrounding the crowning exhibit – an 18-meter-long skeleton of a Basilosaurus Isis whale. There’s also a short documentary about the Wadi Al Hittan Complex.

- Tunis VillageThe small village of Tunis (‘izbat Tunis) is located in the oasis of Fayoum on the way to Wadi Rayan; discover authentic desert adventure on a hill facing the large Qaroun lake. The village overlooks a stunning view of the edge of the desert on the other side of the lake. It is one of the most beautiful places in Egypt. In the 1980s Evelyne Porret, a potter from Switzerland, moved here with her husband Michel Pastore and built a house and pottery studio. She was the first potter in the village and she trained many of the local children in the craft of pottery. Several of her students ended up creating their own pottery studio. Over the last thirty years artists, painters, writers, journalists and others from Cairo and elsewhere have built mud-brick houses in the village; as well as an Art Center which all contribute to Tunis’ lively artistic feel. Today the village includes a School and more than ten Pottery Studios Tunis village has a few well designed eco-lodges and it is the base for many tours and explorations around Fayoum. Fayoum Art Center: is a Non Profit Organization founded by Egyptian artist Mohamed Abla in 2006. It was inspired by the International Summer Academy in Salzburg where Abla taught for several years. Fayoum Art Center is dedicated to connecting artists locally, regionally and internationally through the creation of art. It does so by providing several large studio spaces, an art library, living areas and a communal dining room which fosters collaboration between its participants. The center is also home to the first Caricature Museum in the Middle East, which holds a vast collection of caricatures by artists such as Saroukhan, George El Bahgoury and Ahmed Toughan. The museum has informative panels that describe the exhibits. Tunis Village is home to the annual Pottery Festival which takes place every Autumn. It brings together gifted artists-potters from Tunis, Cairo and other parts of Egypt, traditional artisans from rural villages, as well as creative potters from other countries. The Festival offers participants a unique opportunity to explore the importance and value of different forms of pottery, learn from peers in a cross-cultural environment, create and experiment together, and discuss the challenges and opportunities facing Egyptian potters and pottery today.

- Samuel DunesAuthentic desert adventure at Ghoroud Samuel or known as SAMUEL DUNES; an area of land in the Egyptian Western desert (part of the North African Sahara) which is mostly covered by sand dunes (Arabic: ghoroud) between lakes and mountains. It offers some of the most diversified fields of dune types close to Cairo and is suitable for a single day trip for off roading clubs. This beautiful sand dune area is abundant with opportunities for adventurers, cultural explorers, naturalists, spiritualists, and campers. Ghoroud Samuel is 45km from North to South and about 10km wide on average in the area entirely covered by dunes, with some infiltration by rocks and small plateaus. It is bordered in the North by the Wadi El Rayan road that is immediately south of Lower Rayan lake, and from the South by Gebel ‘As’as. From the East it is bordered by Gebel Qalamon and the Monastery of Saint Samuel the Confessor. From the West, it is bordered by the plateau of Manaqir Qibli. Unlike other areas that have a sand composition with a high percentage of silt, these dunes have very little or no silt/clay grains in them. This makes them very loose and imposes higher challenge for the 4×4 vehicles cruising the area.

- The Magic LakeOne of the most beautiful lakes in Fayoum; discover authentic desert adventure, overlooking sand dunes. This is your chance to freshen up after a long day of hiking, and to witness one of the most eye-catching sunsets. The Magic Lake is located in Wadi El Hitan. It was given this name because the lake changes colors several times each day, the colors depend on the time of day and amount of sunlight it receives. As it is surrounded by desert you can go sand-boarding beside the lake, go swimming or enjoy sitting by the waterfall. The lake contains minerals that may benefit those who have rheumatism. You can also enjoy riding and racing cars through the desert.

- KaranisDiscover authentic desert adventure in one of the largest Greco-Roman cities in Fayoum, built by the Ptolemies in the third century BC. What remains today of the city are two well preserved temples dedicated to crocodile gods and a Roman bath. It also has an interesting museum displaying a wide range of glassware, jewellery and pottery discovered on site. The extensive ruins of ancient Karanis are 25 km North of Madinat Al Fayoum, on the edge of the oasis depression, along the road to Cairo. Founded by the mercenaries of Ptolemy II in the 3rd century BC, this was once a mudbrick settlement with a population in the thousands. Today little of the ancient city remains intact aside from half-buried, crumbling walls scattered across the sand and the two temples. The larger and more interesting temple was built in the 1st century BC and is dedicated to two local crocodile gods, Pnepheros and Petesouchos. The temple also has inscriptions dating to the time of the Roman emperors Nero, Claudius and Vespasian. Less remains of the North temple. There is an ancient pigeon tower similar to those you see throughout Egypt now. In the domestic area near the temple is a bathtub adorned with frescoes. The Museum is next to what was once Lord Cromer’s field house. It has a collection of artefacts from sites around Fayoum. It includes objects from the Pharaonic, Graeco-Roman, Coptic and Islamic eras. There are also columns and stone statuary remnants rescued from Kiman Faris (ancient Crocodilopolis) which was erased by the modern city of Madinat Al Fayoum.

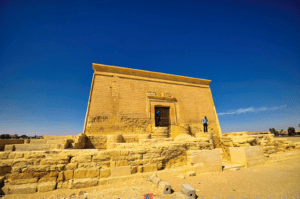

- Qasr QarunAuthentic desert adventure at the Western end of Lake Qarun and just East of the village of Qasr Qarun are the ruins of ancient Dionysias. This was the starting point for caravans to the Western Desert oasis of Bahariya. All that remains of the ancient settlement is a Ptolemaic temple known as Qasr Qarun. It was built in 4 BC and dedicated to Sobek, the crocodile-headed god of Al Fayoum. There are excellent views from the rooftop. The temple is constructed of limestone and there are few inscriptions. Inside are chambers, tunnels and stairs. The main temple is dark inside, but on December 21st of each year an astronomical phenomenon known as “Wonder of the Sun” occurs – when the sun lights illuminate the sanctuary of the temple.

- Medinet MadiMedinet Madi Archaeological site is on a small hill in a strategic position, guarding the South West entrance to the Fayoum about 35 km from Medinet El-Fayoum. The town was called DjA by the ancient Egyptians, during the Greek period it was identified as Narmouthis. A document found here from the ninth century AD mentions Madi, “City of the Past”, as the name of the site. The Middle Kingdom temple is considered one of the most important temples in the Fayoum region due to its reasonable state of preservation and the existence of reliefs on some of its walls and columns. It was dedicated to the triad Sobek (the crocodile god), Renenutet (serpent goddess of harvest) and Horus of Shedet. During the Greco-Roman period it was consecrated to Isis (Thermounis) and Soknopaios. The temple was originally built in the 12th Dynasty by Kings Amenemhat III and IV. It was restored during the 19th Dynasty. During the Ptolemaic period many additions were made to the Northern and Southern sides of the Middle Kingdom temple. The temple’s inner chambers are made of dark sandstone and are the oldest part of the temple and a rare model of Middle Kingdom monumental construction. A papyrus columned portico leads into a sanctuary with three shrines. The middle shrine once housed a large statue of Renenutet, with Amenemhet III and IV standing on either side of her. The Graeco-Roman Temple. The Ptolemaic extension of the temple included the processional way to the South with lions and sphinxes in both Egyptian and Greek style, which passed through a columned kiosk, leading to the older two columned portico. Ptolemy IX Soter II probably added three courtyards, along with other elements. The temple contains a few reliefs and hieroglyphic inscriptions. Coptic texts were uncovered near Medinet Maadi in 1928. Among them was the Manichaean Psalm-book that includes the Psalms of Thomas.

- Deir AzabEl-Azab Monastery, also known as the Monastery of the Virgin Mary, is 6 km south of Medinet El-Fayoum. It is considered one of the most important monasteries in Fayoum because it is the burial place of Anba Abraam, the favorite bishop of Fayoum and Giza from 1882 to 1914. This monastery was built in the 12th century by Peter, the bishop of Fayoum. Very little of the 12th-century original building remains. The monastery contains five churches but there are two principal churches: Abu Seifein is a modern church that contains the remains of the Fayoum Martyrs and other martyrs. The Virgin Mary church contains some of the original building which dates back to the 12th century.

- Abo Seifeen churchThis church is completely modern، and it is characterized by its remarkable domes. This church also contains the remains of the Fayoum Martyrs and other martyrs encased in ornamented red velvet in glass boxes.

- Virgin Mary ChurchFew relics of the original building which dates back to the 12th century still exist in this church. It is dedicated to St. Virgin Mary. The church is rectangular and divided into four aisles by three colonnades every one of them consists of three circular columns. These aisles end with four irregular-shaped sanctuaries on the eastern side of the church and there is a wooden screen that separates these sanctuaries of the church’s aisles. The monastery also houses the museum of Anba Abraam and his burial place.

- El Aioun Monastery (The Monastery of St. Macarius)The Monastery lies in a Rayan Valley protectorate area and is famous for having caves as cells for monks and churches. It also has a natural spring that provides water to the monks and the Monastery farm. Monastic life in this locale goes back to the 4th century when Saint Macarius; the Alexandrian, lived there. Monks remained in Fayoum until the 15th century when they left the area for around five centuries.

- Petrified ForestThe largest petrified forest in the world is located in the north of Lake Qaroun in Gabal Qatrani. It is a home of 40-meter-high trees that have survived in fossilized form for thousands of years. The Petrified Forest is the remnants of a forest that grew 35 million years ago. The trees are perfectly petrified, down to their smallest details, and include marshy plants and aquatic ferns as well. This kind of Petrified wood can be found on every continent but Antarctica. Some well-known petrified wood sites are found in the USA, Argentina, Brazil, China, Indonesia, UK, New Zealand, Australia and Ukraine. The Petrified Forest is now the location of Jebel Qatrani-museum open-air Museum. The Museum laid up in 2018 to display geological artifacts millions of years old found in the Fayoum desert, including Petrified trees, fossilized Whales, Aegyptopithecus, elephants, Phiomia, Palaeomastodon, Arsinoitherium, crocodiles, snakes, and many other well-preserved fossils. The museum was built in early 2018 and yet has to be inaugurated soon. It showcases fossils of both marines.

- Hawara PyramidsBuilt by king Amenemhat III (1843-1797 BC). Although the Pyramid of Hawara was originally covered with white limestone casing, sadly only the mud-brick core remains today, and even the once-famous temple has been quarried, but still has an impressive presence. Herodotus described this temple more than 2000 years ago, when it stood at 300m by 250m (985 ft. by 820 ft.), as a 3000-room labyrinth that surpassed even the Pyramids of Giza. ,The interior of the pyramid, now closed to visitors, revealed several technical developments: corridors were blocked using a series of huge stone portcullises; the burial chamber is carved from a single piece of quartzite; and the chamber was sealed by an ingenious device using sand to lower the roof block into place.

- Pyramid of El LahunAbout 10 km Southeast of Hawara are the ruins of this mud brick pyramid, built by Pharaoh Sesostris II (1880–1874 BC), set on an existing rock outcropping. Ancient tomb robbers stripped it of rock and treasures, except for the solid-gold cobra that is now displayed in the Museum in Cairo.

- Abu Leifa MonasteryAbu Leifa Monastery is cut into a mountain. The inscriptions have revealed that it dates back to 686 AD and was probably founded by St. Panoukhius. The monastery was in use from the 7th through the 9th centuries. It served as a haven for Christians fleeing from persecution. Immediately behind the Qasr El Sagha temple; and visible on the cliff face of the upper portions of the Deir Abu Leifa member giant cross-bedded sandstone, are a similar series of small man-made caves probably used for meditation. The monastery is very primitive, its entrance is cut into the mountain and consists of small caves carved into cliff sides that can be difficult to reach. This Monastery is not inhabited but its best example shows how ancient Monasteries looked before being developed to modern looking.

- Nazla VillageLocated on a branch of Bahr el-Youssef which runs through a deep clay bed In the western part of Fayoum, the river clay is used to hand-make pottery. Potters of Nazla use a very particular technique to make a spherical pot based on a combination of wheel-thrown and hammer-and-anvil; work is carried out according to very old and traditional methods of producing pottery that has not changed much since Pharaonic times. Inside the 20 workshops; there is a hole – a kind of hemispherical scoop in the ground. Straw and clay are mixed together and sometimes with ash. The material is put into the hole then it is hammered and turned at the same time to make large globes. The big pots are allowed to dry a little, and it is only then that the vessels are finished on the wheel.

Only the rims of the large round pots are made on the throwing wheel. These vessels are not a result of mechanical turning but of the turning of the body, the rhythm of the body, and the hole in the ground. The pots of Nazla are archetypes and are therefore in history. Here the history is walking alongside the vessel; on a different but parallel path.

While the Nazla pots are fired, they are fired at fairly low temperatures and the use of straw, mixed with the clay, also inhibits strength. The pots were used in the kitchen to carry and store water and milk, for animal foodstuffs, and for a whole host of purposes. They have less and less utility and there is not a big future. There is a need now to help the potters develop the pots as forms and shapes rather than objects that are supposed to have a utilitarian value. The potters are friendly and can show you the tricks of the trade.

- Ancient Paved RoadThe route to the Qasr El Sagha temple all the way to the ancient basalt quarries of Widan El Faras passes by an ancient road that is reputedly the oldest paved road in the world. The road is dated along with quarry activity as Old Kingdom, with a possibility of it being of Neolithic age; at Widan El Faras the road is fully visible on the surface. The road’s main trunk runs along the foot of the Gebel el-Qatrani escarpment, below the quarry and is joined in several places by short branches coming from different parts of the quarry. The pavement has a uniform width of about 2 m. It is made from a single course of dry-laid, unshaped pieces of whatever stone was close at hand: basalt and sandstone near the quarry, and sandstone, limestone, and silicified wood elsewhere. The total length of the road, including all its branches is nearly 12 km, the last ten of which follow a nearly straight and mostly downward course from Widan el-Faras to its final destination on the shore of an ancient and now extinct lake. The ancient road stands elevated partially above the desert due to relative wind erosion estimated at 3 cm a century.

- Widan El Faras Basalt QuarryA large black basalt quarry exists at the northern edge of Gebel Qatrani, near the two prominent buttes called Widan el-Faras. It was once an Old Kingdom quarry now known to be the source of basalt used for the Old Kingdom pyramid temples. The site stands about 340 meters above sea level. The basalt was loaded onto sleds and transported down the escarpment to the waiting boats at the quay at Qasr al-Sagha. The roadway that led to the quarry was constructed of basalt stone and petrified wood during the Old Kingdom. The quarry road begins at Qasr al-Sagha, turns north, and climbs the escarpment as it moves across the plain, moving directly to Widan al-Faras, 8 kilometers away. Then it skirts the second escarpment to Gebel Qatrani. The western and eastern parts of the quarry are separated by 0.5 km and both contain an excavated bench on top and along the edge of the Gebel el-Qatrani escarpment. The basalt is naturally broken up by cross-cutting fractures with spacing comparable to the sizes of the basalt blocks in pyramid temples. Once a block was isolated, wooden levers and ropes were probably used to move it along the shortest overland route (66 km) to the Nile Valley which is called the ancient paved road. The Widan el-Faras quarries are hard to distinguish, but when you first “see” them, they offer great insight into the Old Kingdom's “project-driven” stone extraction. There are four pyramid temple floors made from basalt – and five individual quarries. This discrepancy can be explained by basalt extracted from the fifth quarry that never reached the pyramid fields by the turbulent end of the Old Kingdom. Because the basalt was taken out – hundreds of blocks are still present in a specific storage place by the quarries and the harbor area by the now almost dried-out Fayoum Lake (present Lake Qarun). The quarries, storage area, and harbor are tied together by a most unusual piece of archaeology: A 12 km long paved road – the earliest paved road in the world. And so the basalt was moved overland down to the old Fayoum Lake and transported on the waterways to the pyramid fields at Giza, Abu Sir, and Saqqara No wonder, then, that Widan el-Faras is such a unique and “readable” quarry landscape, Unfortunately, the quarry is still in use today.

- Qasr El Sagha templeThe site can be reached via a track from Kom Ushim and is about 25 km from the main road. Above the northern shore of Birket Qarun, in a now deserted and inhospitable area at the foot of the desert escarpment towards Gebel Qatrani, is a small uninscribed temple known locally as Qasr el-Sagha. In remote antiquity a forest grew on the escarpment north of the site – petrified remains can still be seen and it is thought that Birket Qarun (ancient Lake Moeris) once extended its northern shore close to the temple in the days when the lake was much larger. Qasr el-Sagha rests on a level platform on the side of the escarpment and was first published by Schweinfurth in 1892 and later visited by Petrie. The date of the temple is a source of debate among scholars, but its plan suggests that the structure was built no later than the Middle Kingdom. Its architecture, however, was interpreted by early explorers as being in the style of Old Kingdom structures. The temple was constructed of limestone blocks of different sizes, which fit tightly together without the use of mortar and with oblique corner joints. The temple was never completed and the walls were left undecorated. The interior contains seven small chambers or shrines and an offering hall. There is also a ‘blind room’ which is completely enclosed and appears to have no entrance. On the flat plain to the south of Qasr el-Sagha, there are several sites of prehistoric villages whose inhabitants seem to have existed by hunting, farming, and fishing. Recently tombs were found with evidence of ancient Egyptian cult practice.

- Dimieh El Sebaa Ancient City ruinsA Greco-Roman city (332 BC-323 AD) founded by Ptolemy II in the third century B.C. on a site that shows evidence of habitation from the Neolithic period. In Ptolemaic times it was at the shore of Lake Moeris (now Lake Qaroun) and the beginning of the caravan routes across Gebel Qatrani and the Western Desert to the Mediterranean Sea coast and then to Greece and Rome. Serving as a port, the site is currently 65 meters higher and 2.5 kilometers beyond the water’s edge. It was like a frontier; inhabited for six centuries and was finally abandoned by the middle of the third century. The ruins cover an area of about 125 acres/0.5 sq. km. The ruins contain two temples, houses located along the processional Avenue of the Lions, underground chambers, streets, 10-meter-high walls, a Roman cemetery that lies 900 yards southwest of the city, and agricultural fields separated by long irrigation canals. Goods from the Fayoum were transported across the lake by boat to be unloaded at the docks of Demieh, stored, or carried up the Avenue of the Lions (370m long), passed the well-preserved remains of houses to a platform on which the ruins of a large temple of the Ptolemaic period dedicated to Soknopaios; assessed for a customs fee, and reloaded on animals for desert caravans. These caravans moved north over Gebel Qatrani and probably via Wadi Natrun, to the Mediterranean and on to Rome. Today one can still see the remains of the road; that connected the temple to the docks on the Lake which ends about a kilometer to the south of the ruins at a quay. The quay has two limestone piers and steps leading south, presumably to the water’s edge. Graeco-Roman city, which is named in the Greek language Soknopaiou Nesos means “The Crocodile Island” are located 8 kilometers to the south of Qasr-el-sagha. At present this place is known as Dimeh-al-Siba (Dimeh of the Lions). It is believed that the city was built in the Ptolemaic Period on the foundation of an ancient settlement. The remains of complex structures; towering above the desert plain were first described by the archeologists Giovanni Battista Belzoni and Karl Lepsius. The artifacts found during the excavations are stored in the Egyptian Museum of Antiquities in Cairo The “Crocodile Island” complex stretches from north to south, covering an area of about 640 meters in length and 320 meters in width. The Temple, the main object of the complex, is located in the southern part of the “island” and covers an area of about 9000 square meters. The whole territory is fenced with white brick walls. The remains of the Temple walls, as well as the interior floors of the Temple, are made of sandstone blocks. There is a road, paved with limestone blocks, taking its beginning at the southern entrance to the Temple complex and stretching towards the Moeris Lake. Its length is 400 meters and its width is about 8 meters. The mudbrick walls of the town can be seen from quite a distance away. They are still 10m high and the site is strewn with debris and pot-sherds which cover the whole space of the temple area.

- Gabal El-MedawaraThe Round Hills (Gabal Al Medawara) near the lake, is ideal for sand boarding. A perfect place to relax contemplate life and discover authentic desert adventure, this area is a reserve of Wadi El Hitan or Whale Valley. Another scenic hiking option overlooking the Magic Lake, and a great place to camp and enjoy the stars.

- Qatrani MountainQatrani mountain which is a 350-meter-high sandstone mountain and a major landmark for travelers and hikers in Fayoum. The Jebel Qatrani area is a treasure trove of fossils that tells the story of the evolution of mammals and primates, starting in the Eocene, notably the ancestry of elephants, hippopotami, hyraxes, lemuroids, monkeys, and anthropoids in addition to multiple representatives of extinct mammalian orders (Embrithopoda, Ptolemaiida) and noteworthy fossil plants. The Jebel Qatrani area of northern Egypt preserves the richest terrestrial mammal-bearing Paleogene exposures in Egypt, if not the entire Afro-Arabian landmass (Sieffert, 2012). Unlike any other known fauna, living or extinct, the mammal community of the JQ consisted of a mixture of endemic groups that have now become extinct or greatly reduced in diversity, plus some important immigrant groups from Eurasia. The site gives evidence of the migration of animals from Africa to Australia and Asia through the occurrence of the genus Varanus; the fossils come from the late Eocene and early Oligocene freshwater deposits of the JQ site, Egypt. The recovery and identification of this material indicate that the genus Varanus arose in Africa, before dispersing to Australia and Asia Fluvial deposits of the early Oligocene age of the JQ site in Egypt document the earliest known diverse avifauna from Africa, comprising at least 13 families and 18 species; this Oligocene avian fauna resembles that of modern tropical African assemblages. The habitat preferences of the constituent species of birds indicate a tropical, swampy, vegetation-choked, fresh-water environment at the time of deposition. Jebel Qatrani fossil site is the only location that compromises two major Paleogene fossil intervals: late Eocene (37-33.9) MYA and early Oligocene (33.9-28,5) MYA. Eocene and Oligocene rocks in the Jebel Qatrani Fossil area are the richest in fossils among all sites. A few fossil species are very limited in numbers; especially some primates, and some species of even-toed mammals are very abundant. The site had the best preservation of Eocene/Oligocene fauna and flora and the largest fossil collections (more than 385 thousand mammals’ jaws, 11500 skulls, and 46 thousand mammal bones); the fossils record in Jebel Qatrani presents 12 orders of placental mammals from the 28 exist today. Among the most important exhibits in the Museum are; Arsinoitherium: Arsinoe beast ( Fayoum Animal ) was named after Queen Arsinoe of Ancient Egypt. This beast was 1.8 meters high at the shoulder and 3 meters long with a pair of enormous horns above the nose and a second pair of tiny knobs-like horns over the eyes. The two large horns on their snouts were hollow and possibly used to produce loud mating calls as well as to compete with rival males. This hefty creature probably spent much of its day chewing on fruits and leaves. Its large size kept it safe from most predators, although creodonts might tackle young individuals. Arsinoitherium lived in small groups and would have been in the water most of the time; it was more closely related to elephants and sea cows than it was to rhinos. The complete skeletons of its fossils were recovered from the north of Lake Qaroun by Beadnell in 1902. Aegyptopithecus: 30 million years ago Aegyptopithecus ( or the Egyptian Monkey) was a tree-dwelling primate that lived in a swampy forest with a great density of other mammals. This early monkey’s weight is estimated at around 6 kilograms; and it ate primarily fruits and showed sexual dimorphism, with males larger and having bigger canines. The enlarged canines served to scare or bite competing males. Aegyptopithecus is widely believed to be near the ancestral line of old-world monkeys and hominoids (humans and apes). It was discovered by Elwyn Simons in 1965 from Quarry M in Jebel Qatrani Formation a few kilometers from the Open Air Museum.

- Siwa OasisThe oasis of Siwa is located at the edge of the Western Desert near the border with Libya, the Qattarra Depression, and the Great Sand Sea. Despite its size (82km by 28km, or 51 by 17 miles), Siwa has around 2,000 acres of cultivated land and a total population of around 33,000. The long trip (about 10 hours from Cairo or Alexandria) is worthwhile because Siwa offers a completely different environment and culture, and several significant archaeological sites. It is an agricultural oasis that is primarily in date palm and olive tree gardens. Dates, olives, olive oil, spring water, and salt are the main products of Siwa. The oasis has hundreds of natural spring water pools, cool or hot, some of which you swim in (others are privately owned by Siwa families and used to irrigate their gardens). Siwa also has large salt lakes where people enjoy sunset or a boat ride. As a result of salt mining, there are also many smaller, vibrantly colored salt pools in which you can float. (Note: don’t shave any part of your body just before visiting and don’t go into the pools with any cuts, because the intensity of the salt will sting). A desert safari into the dunes and open expanses is recommended, with interesting rock formations, beautiful sunsets, and a wealth of stars visible at night. Ancient sites include the Temple of the Oracle at Aghurmi, the Temple at Um Ubeyda, Ain Guba (known as Cleopatra Bath or Spring), and Gebel al-Mawta (Mountain of the Dead) tombs. The people of Siwa are mostly Amazigh (Berber), and their culture and language Siwi are distinct from those of other areas of Egypt, due to the Oasis being relatively isolated for many centuries. To learn more about the culture visit the Siwa House Museum. Siwa is known to have been settled since at least the 10th millennium BC but was historically part of ancient Libya. The earliest evidence of connection with ancient Egypt is in the 26th Dynasty when a necropolis was established. During the Ptolemaic period of Egypt, its ancient Egyptian name was sḫ.t-ỉm3w, "Field of Trees". During his campaign to conquer the Persian Empire, Alexander the Great visited the oasis. His court historians claimed that the Oracle of the Temple confirmed him as both a divine personage and the legitimate Pharaoh of Egypt. The oasis was officially added to Egypt by Muhammad Ali of Egypt in 1819. Shali, the ancient fortress of Siwa, is as fascinating as the more ancient structures in the oasis. It dates back at least 600 years and was built on natural rock and made of kerchief (a salt and earth mix) and palm logs, a building technique that continues in Siwa although it has mostly been replaced by more standard modern construction materials. The most important event in Siwa Oasis is the harvest season. A festival is held around the full moon in October, with many of the men and children camping for several days and nights at Gebel Dakrur (Dakrur Mountain), sharing communally cooked meals and prayers. The festival has historical roots in the ending of conflicts between the people of Siwa. What to see: The center of the main town (called Shali) is dominated by the spectacular shapes of old Shali, a 13th-century earth-built fortress. The fortress provided housing to thousands of people, however a torrent of rain in 1926 caused massive damage to it. Some homes and buildings continued to be in use, including the Old Mosque with its chimney-shaped minaret, however much of the fortress was ruined. In the last 20 years, there has been substantial reconstruction here including homes and hotels, and improvement to the path that leads to the summit of Shali where you can enjoy views across the oasis, a favorite place for sunset watching. Further from the central town, rugged Jebel Dakhrour also offers stunning views, contrasting the verdant oasis with the salt lake Zeitun and the surrounding sand which is famous for its ability to ease rheumatism. Gebel al-Mawta, the Mountain of the Dead, is a hill honeycombed with rock tombs, most of which date back to the 26th Dynasty or the Ptolemaic and Roman times. The Tomb of Si Amun has the most beautiful paintings, with well-preserved reliefs. The Tomb of the Crocodile is also famous for its inscriptions and drawings. The fortified settlement ruins of Aghurmi also offer superb views of the salt lakes of Siwa, the town, and the palm gardens. This is the location of the famous Oracle Temple, the Temple of Jupiter Ammon. Built between 663 and 525 BC, the temple became well known due to Alexander the Great’s visit to the oasis in 332 BC. It is believed that he sought confirmation of a godly heritage. Siwa House Museum contains an interesting display of traditional clothing, jewelry, and crafts typical of the oasis, including the many-layered bridal garments that feature intricate embroidery by Siwa women which has become known internationally. Fatnas Spring is located near the lake edge and is one of the preferred spots for sunset watching. Siwa’s most well-known spring is Ain Guba (Cleopatra’s Bath), a large stone pool fed by spring water. Due to its clean water and beautiful location, it is a popular swimming spot for both locals and tourists. To respect the locals’ views it is advised that women and men dress modestly in shorts and t-shirts rather than brief swimwear here. Bir Wahed is a hot water pool next to a freshwater lake. To soak in Bir Wahed while watching the sunset over the dunes is a great experience. Wearing swimwear here is fine, as the pool is slightly further from the locals and the oasis. There are several other hot spring pools you can also visit.

- Qara Oasis (Gara)Qara Oasis, or Qarat Umm El-Sugheir, which means “Mother of the Little One”, is a picturesque village and one of Egypt’s inhabited oases. It lies at the point where the Egyptian desert tips down into the Qattara Depression. It is 16 km (10 miles) long and 8 km (5 miles) wide, 18,000 km² (6,950 square miles), and 133 meters (436 ft.) below sea level. Unfortunately, the oasis is often disregarded due to its small size in comparison to other oases, with only around 360 people living there. In local folklore, if a newborn arrives, an elder will die shortly after, keeping the population constant. A mud brick village perched on a natural outcropping, it is one of the few remaining fortress towns to be found intact, untouched by modern convenience. Qara can be considered the most isolated of the oases in Egypt. The other oases are affected by civilization to some extent but Gara stays as it is. It has its own Shali (historical fort) and natural springs. Few people make it to Gara, so the people living here are enthusiastic to meet visitors. Children are particularly excited, so you may wish to carry small gifts. Qara is sometimes known as the camp of Alexander because, on his return journey from Siwa, Alexander paused here on the way to Memphis. The Sanusi were in Qara, as was the Axis army. The original town of Qara was in reality a fortress, using the natural defense of the mountain, topped by the outer walls of the homes. The people of Qara live in a very hostile environment and have a difficult time growing crops. They subsist on olives, and dates, which are the most important source of income, and a few vegetables. Beyond the oasis, dominating the horizon is the Mountain of the Milky Horns (Gebel Qarn Al-Laban), a white mountain with several outstanding peaks. Despite its low economic status, Qara is one of the places in the Western Desert where traditional Bedouin hospitality is maintained. The village has a meeting hall where important matters related to the tribe are discussed. Here they also entertain guests who visit, with the Sheikh offering the traditional hospitality of tea on arrival followed by a tour of the oasis.

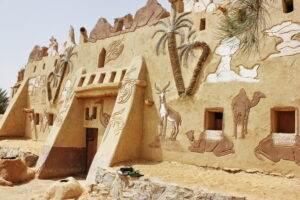

- Farafra OasisThe Oasis of Farafra is a triangular-shaped fertile depression around 3010 sq. km. (1162 sq. mi.) to the northwest of Dakhla and roughly mid-way between Dakhla and Bahariya, with the impenetrable Great Sand Sea bordering the region to the west. The junction of major caravan routes lying in the middle of a vast depression, Farafra owes its fame to the nearby Black Desert and its thermal springs. Farafra is the least populated, with only around 5,000 people, and the most remote of the Western Desert’s oases. Its exposed location made it prone to frequent attacks by Libyans and Bedouin tribes, many of whom eventually settled in the Oasis and now make up much of the population. Farafra’s ancient history is clouded in mystery. Even though it is mentioned in literary sources, Farafra is not noted for its ancient monuments and no archaeological evidence of Pharaonic occupation has yet been found. Mostly inhabited by Bedouins, the small mud-brick houses all have wooden doorways with medieval peg locks. As in other oases, many of Farafra’s houses are painted blue (to ward off the Evil Eye) but here some are also decorated with landscapes, birds, and animals. In recent years, the government has been increasing its efforts to revitalize this region, and the production of olives, dates, apricots, guavas, figs, oranges, apples, and sunflowers is slowly growing. What to see: At the highest point in the vicinity, houses merge imperceptibly into the ruined mud-brick fortress (qasr) that gives the village, Qasr Al-Farafra, its name. It does make an interesting walk within the ruins trying to imagine the generations of Farafronis using this as shelter and protection from external aggression. Possibly built on the site of an original Roman structure and constructed, the present fortress was enlarged or rebuilt during medieval times, after which it contained at least 125 rooms. Next to the qasr is a small well that would have provided the inhabitants with an important water source in times of siege. Unfortunately, the fabric of the building was damaged by rain in the 1950s, adding to its state of collapse, although it is still partly inhabited today. There is also an ancient cemetery near Qasr el-Farafra, where a few un-decorated rock-cut tombs are almost completely buried by sand. Other rock tombs can be seen in areas nearby, some of which were used as dwellings by early Christian hermits, who scratched or painted their crosses on the walls. Not to mention that there is a small hill inside the fortress that you can climb and from there you see the view of the old houses, new red brick houses, the greenery, and the desert. If you visit the qasr on a Thursday morning, you can catch the market where locals sell fruits, vegetables, and other products. The Farafroni women usually handle the market. The extensive palm groves behind Qasr al-Farafra village look especially lovely just before sunset. They are divided into walled gardens planted with olive and fruit trees as well as date palms (whose branches are used to fence the land). You can walk the paths freely, but shouldn’t enter the gardens uninvited. Badr Abdel Moghny is a self-taught artist. Badr’s Museum resembles a Disneyfied desert mansion, with reliefs of camels and farmers decorating its walls and an antique wooden lock on the door. Its dozen-odd rooms exhibit Badr’s rustic sculptures and surreal paintings, stuffed wildlife, weird fossils, and pyrites. His distinctive style of painting and sculpture in mud, stone, and sand has won him foreign admirers; he exhibited successfully in Europe in the early 1990s and later in Cairo. His museum aims to shed light on Farafroni's history, culture, and traditions. Badr also holds workshops where he teaches his guests how to paint with sand and practice sculpture-making. The Roman spring of Ain Bishay bubbles forth from a hillock on the northwest edge of town. It has been developed into an irrigated grove of date palms together with citrus, olive, apricot, and carob trees, and is a cool haven. Farafra has about a hundred wells and natural springs used for irrigation, some of which are also suitable for bathing, like the popular stop Bir Sitta (Well Six), a sulfurous hot spring. Water gushes into a jacuzzi-sized concrete pool and then spills out into a larger tank. This is a good place for a nighttime soak under a sky full of stars with shooting stars flying left and right and the Milky Way galaxy stretching above you. If you’re hanging around in the summer, a plunge in cool Abu Nuss Lake offers instant relief from oppressive afternoons. You might see all kinds of birdlife are drawn to the reedy freshwater. Until a decade ago the New White Desert was off-limits due to the proximity of Ain Della (“Spring of the Shade”), which has played an epic part in the history of the Western Desert as the last waterhole before the Great Sand Sea. Used by raiders and smugglers since antiquity, explorers in the 1920s and 1930s, and the Long Range Desert Group in World War II, it now has a garrison of Egyptian Border Guards. The spring water is sweet to drink and allows the soldiers the luxury of showers at their barracks in the middle of nowhere.

- Dakhla OasisLuxuriant and abounding in water, Dakhla was the ancient capital of the oases during the Pharaonic age. Covering around 2000km2 (772 sq. miles), it supports 75,000 people in 14 settlements, and is particularly lush, with around 45% of its land being cultivated. Dakhla lies in a depression that is bordered to the north by an impressive scarp but is open on its east and west sides. To the east, it extends into the Kharga depression, while to the west it is delimited by the large dunes that mark the beginning of the Great Sand Sea. It lies in the center of important caravan routes that connect it directly to the Farafra and Kharga oases, as well as Libya and the Nile Valley. Considered remote, even in the eyes of the Egyptians, Dakhla Oasis is home to farmers and Bedouins who have been attracted to its solitude and abundance of water. These two factors have attracted the attention of farmers who could not start their farms in bigger cities, and hence have moved here. Most of its residents are farmers who constantly fight the battle of the dunes that threaten their fields and orchards. The fields and gardens are filled mostly with mulberry trees, date palms, figs, and citrus fruits. Local farmers wear straw sombreros, seldom seen elsewhere in Egypt. Dakhla has retained most of its culture and charm even though it has almost doubled in size, and government funding and technical training have revitalized the economy. It is the only place in Egypt where new water wheels driven by buffaloes are constructed. Most villages have spread down from their original hilltop maze of medieval houses and covered streets into a roadside struggle of breeze-block houses, schools, and other public buildings. The region has been inhabited since prehistoric times, with fossilized bones hinting at human habitation dating back almost 150,000 years. In Neolithic times, Dakhla was the site of a vast lake, and rock paintings show that elephants, zebras, and ostriches wandered its shores. As the area dried up, inhabitants migrated east to become the earliest settlers of the Nile Valley. In Pharaonic times, Dakhla retained several settlements and was a fertile land producing wine, fruit, and grains. The Romans, and later Christians, left their mark by building over older settlements, and during medieval times the towns were fortified to protect them from Bedouin and Arab raids. Besides Islamic architecture, Dakhla has Pharaonic, Roman, and Coptic antiquities, dunes, palm groves, and hot springs to explore. Dakhla Oasis is dominated on its northern horizon by a wall of rose-colored rock. Fertile cultivated areas growing rice, peanuts, and fruit are dotted between sand dunes along the roads from Farafra and Kharga in this area of outstanding natural beauty. What to see: The Mut Village is the most important of the 16 villages in the Dakhla oasis, inhabited today by around 80,000 people, and is considered the capital. Its name derives from Goddess Mut, the wife of Amun (the supreme deity in the Theban pantheon). In the highest part of the town is the “old city”, with its sun-dried brick houses separated by narrow passageways and gates that were locked at night. To the Southwest of Mut are the remains of Mut el-Khorab, “Mut the Ruined” " an Ancient Roman period settlement where poorly preserved remains of mud-brick walls measuring up to 3m (10 ft) high loom over pits left by treasure-hunters, and where Fennec foxes dwell in burrows, emerging to hunt at dusk. It was inhabited up to the early 20th century. Mut’s Ethnographic Museum is small, but well-organized that captures a complete picture of the life of an oasis dweller. It is ordered like a family dwelling, with household objects on the walls and a complex wooden lock on the palm-log door. Its seven rooms contain clay figures by the Khargan artist Mabrouk, presenting scenes from village life, such as preparing the bride and celebrating the pilgrim’s return from Mecca. These are two scenes that remain part of Oasis’s life today. There are several hot sulfur pools around the town of Mut, but the easiest to reach is Bir Talatta. It’s at the site of the small Mut Inn; it is like a large swimming pool of brown, sulfur- and iron-rich water, flowing from a depth of over 1000m (3281 ft.), this is a perfect place to relax after a hard day’s sightseeing. The pool’s strangely colored water is both warm and rather relaxing, though it may stain clothes. Bir al-Gebel is a spring set among breathtaking desert scenery. It has been turned into a day-trip destination where blaring music and hundreds of schoolchildren easily overwhelm any ambiance it might have had. It’s best to come in the evening when it’s quieter and the stars blaze across the night sky. Deir al-Hagar temple is a restored Roman sandstone temple. It is one of the most complete Roman monuments in Dakhla. Dedicated to the Theban triad (Amun, Mut, and Khonsu), and the God of the Oasis, Seth, it was built between the Reigns of Nero (54–68 AD) and Domitian (81–96 AD). The cartouches of Nero, Vespasian, and Titus can be seen in the hypostyle hall, which has also been inscribed by almost every 19th-century explorer who passed through the oasis. Also visible are the names of the famous desert travellers Edmonstone, Drovetti, and Houghton. Its Arabic name is “Stone Monastery”, and it once served as a Coptic monastery. Al-Qasr ‘the Fortress’ is a must: an amazing fortified Medieval Islamic settlement, founded around the end of the 12th century AD by the Ayyubids, over the remains of an earlier Roman Period settlement. It may be the longest continually inhabited site in the oasis; three or four families still live in the mud-brick old town crowning a ridge above palm groves and a salt lake, set back from New Qasr beside the highway. During medieval times, the fortified town was thought to have been the Capital of the Oasis, constructed in a defensive position against marauding invaders from the South and the West. Its streets were divided into quarters that could be closed off at night by barred gates. The narrow covered streets have changed little since these times. Beyond the twelfth-century Nasr el-Din Mosque, there is a three-story mud-brick minaret, measuring 21 m. (69ft.) tall. After this, you enter a maze of high-walled alleyways and gloomy covered passages. Over thirty houses here have acacia-wood lintels whose cursive or Kufic inscriptions name the builders or occupants (the oldest dates from 1518): look out for doorways with Pharaonic stonework and arabesque carvings, archways with ablaq brickwork, and a frieze painted in one of the passageways. Near the House of Abu Nafir – built over a Ptolemaic temple, with hieroglyphics on its door jambs – is a donkey-powered grain mill. Further north, a rooftop mala’af or air-scoop incorporated into a long T-shaped passage conveys breezes into the labyrinth. Beyond is a tenth-century madrassa (school and court) featuring painted liwans, niches for legal texts, cells for felons, and a beam above the door for whippings. The maze of alleyways also harbors a restored blacksmith’s forge. Bashindi Village is a well-preserved village of Pharaonic design and hosts an Islamic cemetery as well as Roman tombs, whose name derives from Pasha Hindi (an Indian prince), who presumably settled here during the 11th -12th century. He was a medieval sheikh who is now buried in the local cemetery at the back of the village. The cemetery dates back to Roman times, and the brick-domed tomb of Pasha Hindi itself is built atop a Roman structure. Empty sarcophagi separate it from the most significant sandstone Tomb of Kitines (2nd century AD); it was occupied by Senussi soldiers during WWI and by a village family after that. It has some funerary reliefs which have survived. Tombs also form the foundations of many of the village houses, which are painted pale blue or buttercup yellow with floral friezes and hajj scenes, merging into the ground in graceful curves. The Balat village was an important Old Kingdom town, with its three-hundred-year-old mosque upheld by palm trunks and a maze of twisting covered streets that protect the villagers from sun and sandstorms, and once prevented invaders from entering on horseback. The village of Balat itself is picturesque and has changed very little from medieval times: the village’s mud-brick houses are painted salmon, terracotta, or pale blue, with carved lintels, and wooden peg-locks. Although the oldest houses in Balat village date back only to the Mamluke times, this locality was a Pharaonic seat of government as long ago as 2500 BC, when the oasis prospered through trade with Kush (Ancient Nubia). “Qila al-Dabba” is Balat’s ancient necropolis; there are the 7 mastabas (mud-brick structures above tombs that were the basis for later pyramids), which belonged to important Old Kingdom governors of the oasis. The most notable of them, the largest, which stands over 10m (33 ft.) high, belongs to the governor Khenitka who served during the rule of Pepi II, 6th dynasty (2300-2206 BC) where funeral artifacts, including gold jewelry was found (these are now in the Museum of the New Valley in Kharga Oasis). Northeast of the necropolis is Ain Asil (spring of the origin) where a fortress and farming community existed from the Old Kingdom until Ptolemaic times. This has proved to be one of the best-preserved examples in Egypt of an Old Kingdom town, with important remains of a governor’s palace, houses, and workshops. The Muzawaka (well-decorated) Tombs were discovered in 1908. They have not yet been entirely excavated and studied, but are known to consist of a series of over 300 rock-hewn tombs. However, the site is renowned mostly for the 2 frescoed tombs (Petosiris and andPetubastis) which are completely decorated with paintings, whose colors have been perfectly preserved, it contains all the main themes of the Ancient Egyptian Tombs, but are represented in the Greco-Roman style, dating to the 1st – 2nd century AD. Unfortunately, they are now closed for restorations. Asmant Al-Khorab, or “Asmant the Ruined” is the local name of the ancient town of Kellis, a Roman and Coptic town inhabited for seven centuries, whose temples and churches mark the shift from Pagan Rome to Byzantine Christianity. Excavations have unearthed the remains of aqueducts, farmhouses, and tombs, including 34 mummies and wooden codices, casting light on religion and daily life in the third century AD. Unfortunately, they are now closed for restorations. Budkhulu is the old quarter of covered streets and houses with carved lintels, a ruined Ayyubid mosque with a pepper pot minaret, and a palm-frond pulpit. Also visible on the hill as you approach is a Turkish cemetery with tombs shaped like bathtubs, grave markers in the form of ziggurats, and domed shrines: the freshly painted one belongs to a revered local sheikh, Tawfiq Abdel Aziz. Qalamoun village dates back to Pharaonic times, with many families descended from Mamluke and Turkish officials having once been stationed here. Its hilltop cemetery affords fine views of the surrounding countryside. Before reaching Tineida village, there are many Prehistoric rock carvings; petroglyphs of camels, giraffes, ostriches, and tribal symbols. The soft sandstone rocks are well-preserved, as well as the name of Jarvis (British governor of Dakhla and Kharga in the 1930s) and many others.

- Kharga OasisKharga Oasis is Egypt’s largest oasis, with a depression of around 376,505 km2 (145,174 miles2), which has been inhabited since prehistoric times. Its modern city, Qasr Kharga, houses 200,000 people including 1,000 Nubians who moved here after the creation of Lake Nasser. It is the nearest of the oases to Luxor and the capital of the New Valley Governorate (comprising of Kharga, Dakhla, and Farafra oases). In ancient times, a lake occupied a large part of the depression and the thick deposits of sandy clay then lay down, which now forms the bulk of the cultivated land. Historical references to expeditions into Kharga Oasis go back as far as the Old Kingdom, but little evidence remains in Kharga today of life in the Pharaonic times. The chain of at least 20 forts, which vary in size and function from large settlements to garrison towns, indicates its importance through the ages. The practice of using Kharga Oasis as a colony for exiles continued throughout Roman times and into the Christian era. Many early Christian bishops were banished here and the oasis soon became a refuge for Christian hermits who often lived in isolated tombs or caves in the desert. Kharga is connected to the Nile Valley by two main routes, one from Armant, near Luxor, to Baris, in the South of the region, and the second from Asyut to Kharga City in the North. The main source of income in the oasis is from agriculture, the cultivation of dates, cereals, rice, and vegetables, which are sent to markets in the Nile Valley. Kharga’s main craft is basket and mat-making from the leaves and fibers of the palm trees. Dates play an important part in the social calendar. The City Day (Oct 3) celebrates the beginning of the date harvest, and the marriage season is also timed to coincide with the flowering of the date crop (from July until harvest time). What to see: The Museum of the New Valley was designed to resemble the architecture of nearby Bagawat Coptic Necropolis. This two-story museum houses a small but interesting selection of archaeological finds from around Al-Kharga and Dakhla Oases. Al-Bagawat Necropolis is one of the earliest surviving and best-preserved Christian cemeteries in the world. Consisting of 263 mud-brick chapels spread over a hilltop, it was used for Christian burials between the third and sixth centuries (it was later used by the followers of Bishop Nestorius, who was exiled to Kharga for heresy). The chapels embody diverse forms of mud-brick vaulting or Roman-influenced portals but are best known for their Coptic murals. A few have vivid murals of biblical scenes inside and some have ornate facades. Adam and Eve, Noah’s Ark, Abraham, and Isaac populate the dome of the fifth-century Chapel of Peace near the entrance to the necropolis. Further north, Roman-looking pharaonic troops pursue the Jews, led by Moses, out of Egypt, in the Chapel of the Exodus. In the center is a church dating back to the 11th century AD. Al-Kashef Monastery, named after a Mamluke governor, has been strategically placed to overlook what was one of the most important crossroads of the Western Desert – the point where the Darb al-Ghabari from Dakhla crossed the Darb al-Arba’een. The magnificent mud-brick remains date back to the early Christian era. Once five stories high, much of it has collapsed, but you can see the tops of the arched corridors that crisscrossed the building. In the valley below you can see the ruins of a small church or hermitage, with Greek texts on the walls of the nave and the tiny cells where the monks slept. Hibis Temple is the largest temple in any of the oases. The town of Hibis was the capital of the oasis in the ancient days, but all that remains today is the well-preserved limestone temple, once sitting on the edge of a sacred lake. Dedicated to the God Amun-Re, construction of the temple began during the 26th dynasty, reign of the ruler Psammetichus II (595-589 BC), though the temple was enlarged and the decorations and a colonnade were added over the next 300 years, till the reign of Ptolemy II (285-343 BC). The temple is well preserved and contains an avenue of sphinxes and an eight-columned pavilion. Entering through the four gateways brings you to the colonnaded court, the hypostyle hall, and the sanctuary. The temple was reconstructed after a $20 million conservation fiasco when it was dismantled to move it to higher ground. Qasr Al Ghweita Temple (fortress of the small garden) is a fortified hilltop temple from the late period with a commanding view of the area, which was intensively farmed in Ancient Times. Its 10m (33 ft.) high walls enclose a sandstone temple dedicated to the Theban Triad (Amun, Mut, and Khonsu), built by Darius I, 27thDynasty, and was completed by the Ptolemeis (Ptolemy III, IV, and X). The temple ruins include a pronaaos with elegant columns, a hypostyle hall, and a sanctuary. It was later incorporated into a fortress during the Roman period. Qasr Al-Zayan Temple is a Roman temple that lends its name to a still-thriving village built over the ancient town of Tchonemyris, one of the largest and most important ancient settlements in Kharga Oasis. The ruins of which have not yet been excavated. This proximity to daily life helps you imagine it as a bustling settlement in antiquity. Dedicated to Amun-Re, the temple is enclosed within a mud-brick fortress, together with living quarters for the garrison, a cistern, and a bakery. The plain hereabouts is 18m. (59 ft.) Below sea level, the lowest point in Kharga Oasis. It was constructed during the Ptolemaic time and there is an inscription that indicates that the temple was restored during the reign of Emperor Antoninus (138-161 AD). Nadura Temple is situated on a 135 m. (443 ft.) high hill in the desert. Its eroded sandstone wall and pronaos aren’t anything special, but it has strategic views of the area and once doubled as a fortified lookout, as suggested by its name, Nadura, meaning ‘lookout’. Built during the reign of Roman emperor Antoninus Caesar (138-161 AD), Nadura is typical of the Roman temple-forts that once protected the oasis from desert raiders. Even though it is now badly ruined, the superb vistas here are ideal for sunset adulation. Al-Deir Fort is the best-preserved and most accessible of Kharga’s Roman forts, which once guarded the caravan route at “Darb al-Arba‘ in the forty-day track to the Nile. Built during the reign of the Byzantine emperor Diocletian (284–305 AD), the fort was built of mud brick, and its twelve rounded towers are connected by a gallery, with numerous rooms featuring graffiti drawn by generations of Roman, Coptic Christian, Turkish, and British soldiers. Its name means ‘monastery’, and was used as such during the Christian era. Later, both Turkish and British troops occupied the fortress. There is a necropolis and the ruins of a church to the west of the fortress. Around the fortress are the ruins of an ancient town where two buildings still stand. The escarpment is the small temple that was later used as a church. The abandoned railway visible in the distance was built by the British between 1906 and 1908, but it has been gradually blocked by advancing dunes. Qasr Al-Labeka Settlement lies in an isolated part of the desert. It was built by the Romans at the other end of the caravan route. It is the nearest site where you can see the amazing system of underground aqueducts, known as manafis that drew on groundwater like the qanats of ancient Persia. The site contains two temples that lie half-buried in the sand, an imposing fort, and a group of decorated tombs. Several buildings once surrounded the fortress and to the south are the silted remains of a large well, an ancient spring, still surrounded by palm, acacia, and tamarisk trees, which would have provided water for the fort and settlement. The size of the well suggests that a large community lived here, which was served by a series of aqueducts, built to take the water out to the cultivated fields. But the fortress itself has never been excavated. In Gebel al-Tayr, “the Mountain of the Birds”, there is graffiti and inscriptions dating to as early as prehistoric times. However, on the western side, a path leads to the top of the mountain through a grotto, and here, Coptic paintings, prayers, and invocations dating from the fourth, fifth and tenth centuries may be found. These inscriptions, which include Demotic and Greek script, were mostly left by hermits who lived in the surrounding caves and can be identified by a cross. At the top of this mountain, we find the Cave of Mary, obviously a sacred site during The Christian Era. There is considerable graffiti, including some that predate The Christian era, but among the etchings is a painting of The Madonna and Child, along with a prayer in alternating red and yellow lines. Ain Umm Dabadib Village is the largest and oldest Roman/Byzantine village in the oasis, covering over 200 sq. km (77 sq. mi.). It includes a ruined Roman mud-brick fortress, ruins of Byzantine churches and tombs, but is most remarkable for its underground aqueducts, the deepest being 53m (174 ft.) beneath the surface and the longest-running is 4.6 km long (3 mi.), with vents for cleaning and repairs every few so often that are covered by large, flat stones. The site is typical of oases fortresses, which were always near a spring. Baris Oasis is named after the French capital, though its foraging goats and unpaved streets make a mockery of a billboard welcoming visitors to “Paris”. It was once one of the most important trading centers along the 40-day track “Darb al-Arba’een”, but there is little left to remind you of that. There is little to see apart from the mud-brick houses of “Baris al-Gedida”, north of the original town. Hassan Fathy, Egypt’s most influential modern architect, designed the houses using traditional methods and materials and intended Baris al-Gedida to be a model for other new settlements, but work stopped at the outbreak of the Six-Day War of 1967 and only two houses and some public spaces have ever been completed. Dush Temple and Fortress is an imposing Roman temple-fortress completed around 177AD, on the site of the Ancient town of Kysis. Dush was a border town strategically placed at the intersection of five desert tracks of caravan routes and one of the southern gateways to Egypt. As a result, it was solidly built and heavily garrisoned, now partially buried in the sands, with mud-brick walls up to 6 m. (20 ft.) high, with four or five more stories lying underground. A 1st-century sandstone temple abutting the fortress was dedicated to Isis and Serapis. The gold decorations that once covered parts of the temple and earned it renown have long gone, but there is still some decoration on the inner stone walls. The fortress formerly protected the Ancient town of Kysis, an agricultural settlement enriched by the 40 Days Road that had potters, jewelers, and brothels.