Luxor

Luxor has been known as Thebes, the great capital of the Egyptian Empire; Waset, meaning “city of the scepter”; Ta ipet, meaning “the shrine”; the “city of 100 gates,” and many other names throughout its history. Luxor is derived from the Arabic word for “palaces.”

It rose to prominence around 3000 BCE and eventually became Ancient Egypt’s political, military, and religious capital for more than 1500 years. It is an important tourism center today, as it is home to a large number of the country’s architectural monuments.

It was the ancient kingdom’s capital as Thebes; today, It is known as the world’s greatest open-air museum, housing some of Egypt’s most famous temples, tombs, and monuments.

Luxor has an unrivaled number of ancient Egyptian monuments. The 3,400-year-old Luxor Temple and the Karnak Temple Complex are among its highlights, as are the necropolises of the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens, and the massive stone statues known as the Colossi of Menmon.

It is a small city and this allows visitors to get around as easily by taxi as by horse-drawn carriage. While horse-drawn carriages are popular with tourists, renting a bike can also be a fun way to see the city sights during the day (and not during the hottest times of the year).

Luxor

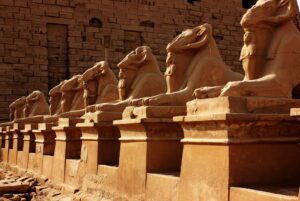

- Karnak TempleKarnak is huge; the site covers more than 100 hectares (247 acres). Construction at Karnak began during the reign of Senusret I in the Middle Kingdom (2000–1700 BC) and continued into the Ptolemaic era (305–30 BC). Most of the remaining structures are from the New Kingdom, and these include remnants of temples, chapels, pylons, and other structures. Most other temples in Egypt were not constructed and used over such a long time period with many rulers involved in construction here. Although it does not have many unique features, it is its size and variety within the site that make it extraordinary. In addition, the gods and goddesses represented here include some of the earliest worshiped as well as those who were favored by much later rulers and the religious hierarchy. The central area is dedicated to the god Amun-Ra. The area immediately around his main sanctuary was known as “Ipet-Sun,” which means “the most select of places.” South of the central area is a smaller area dedicated to the goddess Mut. To the north is another area dedicated to the god of war, Montu. To the east is an area dedicated to the Aten, the sun disk. The UCLA Digital Karnak project reconstructed and modelled the changes to the temple: http://wayback.archive-it.org/7877/20160919152317/http://dlib.etc.ucla.edu/projects/Karnak

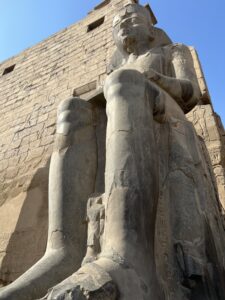

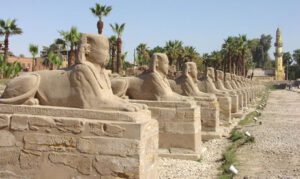

- Luxor TempleLuxor Temple is located approximately three kilometers south of Karnak Temple. These temples were linked by a processional way bordered with sphinxes, now known as the Avenue of the Sphinxes. As was the case with Karnak Temple, Luxor Temple was constructed by many rulers. Unlike most other ancient Egyptian temples, it is not laid out on an east–west axis, but is oriented towards Karnak. The reason is that Luxor Temple was the main venue for one of the most important ancient Egyptian religious celebrations - the Opet Festival - when the cult images of Amun, his wife Mut, and their son, the lunar god Khonsu, were taken from their temples in Karnak, and transported in a grand procession to Luxor Temple so they could visit the god that resides there, Amenemopet. This festival was recently reenacted when the restored Avenue of the Sphinxes was opened. The oldest existing structure in Luxor Temple, a shrine, dates to the reign of Hatshepsut (1473–1458 BC). The core of the temple was built by Amenhotep III (c.1390–1352 BC). Amenhotep III also built the Great Colonnade, almost 61 meters (200 feet) long, with 28 columns. The decoration of this was completed by Tutankhamun (1336–1327 BC) and Horemheb (1323–1295 BC). Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) made many additions, including a peristyle courtyard and a massive pylon, a gate with two towers that formed the entrance into temples, many colossal statues, and a pair of obelisks 25 meters (82 feet) in height (only one remains in place; the other was taken to the Place de la Concorde in Paris). In the late third century AD the Romans built a fort around the temple, and the first room beyond the hypostyle hall of Amenhotep III became its sanctuary. The original wall reliefs were covered with plaster and painted in the GraecoRoman artistic style, depicting Emperor Diocletian (284–305 AD) and his three coregents. Many of the side walls of the temple were removed subsequent to the rule of the pharaohs and used for building other structures.

- Valley of the KingsWe continue inland to the Valley of the Kings which is part of the necropolis of ancient Thebes. This is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. For more than a thousand year the kings, queens and nobles of the New Kingdom (1500 – 1070 BC) chose to be buried here. The tombs are carved into the limestone rock of a wadi (valley) and the surrounding landscape is in itself awesome. Those buried here hoped their tombs would be safer than those of earlier royalty and courtiers who had been buried in pyramids and other more exposed tombs. Many of the tombs are exquisitely decorated, they show scenes of everyday life and of the spiritual life the ancient Egyptians believed they would be part of after their physical death. The tombs were also filled with objects or depictions of objects that the occupants of each tomb would need including food, furniture, clothes and jewelry. There are so many tombs worth visiting that today’s visit to three will hopefully encourage you to return to visit more of the Valley of the Kings with us. For more information about the West bank royal necropolis of the New Kingdom https://thebanmappingproject.com

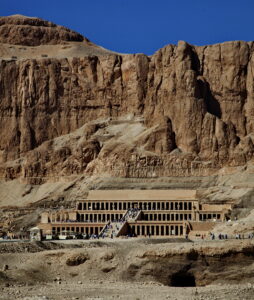

- Hatshepsut templeDuring her reign, the female pharaoh Hatshepsut (1473–1458 BC) built a mortuary temple at Deir el Bahari, situated directly across the Nile from Karnak Temple, which was the main sanctuary of the god Amun. Djeser-djeseru, “the Holy of Holies,” was designed by the chief steward of Amun, Senenmut. It nestles under towering cliffs, and many find it one of the most beautiful of all the temples constructed in Egypt. Hatshepsut clearly realized that as a woman in what was usually a male power role, impressive structures that bettered those of previous rulers would help to impress people and legitimize her reign. The temple was modeled after the mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II (2061–2010 BC), who founded the 11th Dynasty. His temple was built during his reign at Deir el-Bahri, and was the first structure there. It was an innovative concept as it was planned to be both a tomb and a temple. Hatshepsut chose a larger interpretation of this temple, positioned next to it, to illustrate her connection to powerful rulers who preceded her and her own power. Her temple has three levels. On the top level, beyond the portico, is an open courtyard, with statues of Hatshepsut as Osiris, the god of the dead. The temple includes areas for the cults of her father, Thutmose I, the goddess Hathor, and the god Anubis. An altar open to the sky was dedicated to the cult of the solar god RaHorakhty. Hatsepsut claimed as her true father, has a sanctuary dedicated to him at the far end of the upper courtyard, on the temple’s central axis. Painted reliefs on the temple walls depict rituals and religious festivals. Reliefs on the middle platform include Hatshepsut’s expedition to Punt.

- Colossi of MemnonAs we start exploring the West Bank, these two imposing sandstone statues indicate the site of the mortuary temple of 18th dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep III (1386–1353 BC) and were completed in 1350 BC. The statues of the seated ruler are 18 meters (59 feet) high and each is estimated to weigh 653 tonnes (720 tonnes). The temple is the largest on the west bank and continues to be excavated. You can see this underway behind the statues. Archaeologists believe the single sandstone blocks from which each statue was carved were quarried near Cairo and transported to Thebes. If the statues were a tribute to Amenhotep III and guarded his temple, why are they known by the name Memnon? During Greco-Roman times, they were associated with the Ethiopian king, Memnon, who was considered a hero by the Greeks. Although he was killed at Troy by the Greek Achilles, Memnon fought on the side of the Trojans against the Greeks. His courage won the approval of the GreeksThe complex was referred to by Greek writers as the Memnonium. It was reported that at sunrise, the northern statue would emit a whistling sound, possibly because of a crack in its body that resulted from an earthquake. Ancient Greek and Roman visitors thought hearing the statue was a positive omen. The statue was repaired in the 3rd century AD and the sound was not heard again.

- Valley of the QueensThe second royal necropolis in Thebes- The Valley Of The Queens is situated just a few kilometers from the Valley of the Kings. There are nearly 80 tombs in the Valley of the Queens. They belonged to Queens, Princes, and other members of the royal families of the18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties (1569-1081BC) It is not in the same condition and is no comparison to the Valley of the Kings but still holds vital keys to our history. What to see: There are three tombs open to the public: the tomb of queen Titi (badly damaged) and two tombs of royal children – Amenherkhepshef and Khaemwaset Tomb of Nefertari: Favourite Queen of RamsesII, Hailed as the finest tomb in the Theban necropolis – and in all of Egypt for its design and its brilliantly coloured painted decorations. Every centimeter of the walls in the tomb’s three chambers and connecting corridors are adorned with colourful scenes of Nefertari. The ceiling of the tomb is festooned with golden stars. Her tomb reflects the queen’s position in the eyes of her husband in the beauty of its construction, its vivid colours, and unusual scenes, and the many favourable epitaphs which describe her beauty and her sweet and charming nature. There is no limited number of tickets available per day, however only 10 minutes inside the tomb is permitted. Entry is 1,600 Egyptian pounds, with no discount for children or students. Tomb of Amunherkhepshef: After Nefertari’s, this is the best tomb in the Valley of the Queens to view with its beautiful, well-preserved reliefs. Amunherkhepshef, the son of Ramses III, was in his teens when he died. On the walls of the tomb, Ramses holds his son’s hand to introduce him to the gods that will help him on his journey to the afterlife. A glass case displays a mummified fetus that his mother aborted through grief at Amunhirkhepshef’s death, and is entombed with her son. Tomb of Khaemwaset: Another son of Ramses III, Khaem-waset also died young. His tomb is filled with well-preserved, brightly colored reliefs. Like Amunherkhepshef’s tomb, Scenes in Khaem-weset’s tomb show him being presented to the guardians of the gates to the afterlife along with his father.

- Nobles tombsWhile the royal tombs were hidden away in a secluded valley of the kings, Noble’s tombs are closer to the surface of the hills overlooking The Nile. Whilst the pharaohs decorated their tombs with cryptic passages from The Book of the Dead to guide them through the afterlife, the nobles, intent on letting the good life continue after their death, decorated their tombs with wonderfully detailed scenes of their daily lives. The pharaohs’ tombs were sealed and guarded; the nobles’ were left open for their descendants to make funerary offerings. Given more freedom of expression, the artists excelled themselves with vivid paintings on stucco. There are more than 400 tombs belonging to nobles from the 6th dynasty to the Greco-Roman period (2374 BC-337 AD). What to see: There are 6 groups of tombs open to the public, each group requires a separate ticket: Dra' Abu el-Naga' - Roy and Shuroy Khokha - 3 tombs El-Assasif - tomb of Pabasa Menna and Nakht Ramose, Userhat, Khaemhat Sennefer and Rekhmire NOTE: the tomb of Rekhmy Ra closed recently. Ramose, Userhat and Khaemhat tombs: Ramose was the governor of Thebes immediately before and after the Amarna revolution. His spacious tomb is one of the few monuments which capture the moment of transition from Amun- to Aten-worship, featuring both classical and Amarna-style in highly elegant bas-reliefs. In the Tomb of Userhat there is an unusual scene of a barber trimming customers beneath a tree, hunting gazelles, hares, and jackals, wine-making, harvesting, herding, branding cattle, and collecting grain for the royal storehouse. The Tomb of Khaemhat has scenes of the complete set of instruments for the Opening of the Mouth ceremony, and a painting of the Goddess Hathor breastfeeding a boy-king, surrounded by sacred cows. This group is considered the best of the other groups. Sennofer and Rekhmire tombs: Tomb of Sennofer, also known as ‘Tomb of the Vineyards’, gets its name from the beautiful decoration on the ceilings which give the impression of standing under an arbor hung with big bunches of grapes. Most of the vivid scenes depict Sennofer and all the different women in his life, including his wife, daughters, and his wet nurse. The reliefs in the tomb of Rekhmire depict Rekhmire collecting taxes and receiving gifts from foreign lands: the panther and giraffe are gifts from Nubia; the elephant, horses, and chariot are from Syria; and the expensive vases come from Crete and the Aegean Islands. Third group: (Nakht & Menna tombs): The walls of the tomb of Nakht have some of the best-known examples of everyday country life. It contains drawings of the reliefs (which are covered in glass).To one side, Nakht supervises the harvest in a scene replete with vivid details. It has the famous banqueting scene, where sinuous dancers and a blind harpist entertain friends of the deceased. The Tomb of Menna has some beautiful and highly colourful wall paintings, decorated with scenes of rural life, representing Menna supervising field labourers (notice the two girls pulling each other’s hair), feasts, and making offerings with his wife. It has vividly detailed scenes of farming, hunting, fishing, and feasting. New discoveries are being made constantly, and the number of available tombs to visit is increasing.

- The Ancient workmen village (Deir El Medina).Deir el–Medina is the Arabic name for the village where the craftsmen and artisans who worked on the tombs and other monuments of the West bank lived, including those in the Valley of the Kings and Queens. From the village, it was a half-hour walk to the tombs. The village was in continuous use until the end of the New Kingdom (1069 BC). In the Christian era, monks lived here. They took over the Temple of Hathor as a cloister, and it was referred to as Deir el Medina, “Monastery of the Town”. Subsequently, this name was used to refer to all of the site. Deir el Medina was a planned community, founded by Amenhotep I (1541–1520 BC) specifically for the workers on royal tombs. It is an important site due to the abundant information it has given about the daily lives of those who lived here. Serious excavation began in 1905 AD and continued throughout the 20th century. At the time when the tomb of Tutankhamun revealed more about how royalty lived, at Deir el Medina, the lives of the workers responsible for the magnificent tombs were coming to light. On the east bank of Luxor, bookending the modern city, are the ancient Theban temples of Karnak and Luxor, with the Avenue of Sphinxes and Luxor Museum between them.

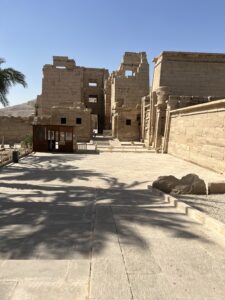

- Habu templeIt features the impressive mortuary temple of Ramses III and also encloses a well-preserved pharaonic palace. The site is unique because it is one of the few where you can find the resting house of a king, giving insights into their daily life. The site was a complex of temples dating from the beginning of the New Kingdom (1569 BC). A temple to Amun was built here by Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. Then, Ramesses III also chose this site as the location of his mortuary temple and commissioned a massive mud-brick enclosure around the entire site; within this were included storehouses, workshops, administrative offices, and residences of priests and officials. The walls sheltered the entire population of Thebes during the foreign invasions of the 21st Dynasty (1081–711) and for three centuries afterward, they protected the Coptic population. The temple precinct is about 214 meters (700 feet) by 305 meters (1,000 feet). The reliefs at the front of the temple depict Ramses III as a victor in several wars. Attached to the temple is one of the few king’s houses remaining. The throne room and other spaces are well preserved. You will also see the remains of an early Christian basilica and a small sacred lake. The history of Medinet Habu Medinet Habu (Habu’s Town) is the Arabic name for the gigantic Mortuary Temple of Ramses III, a structure second only to Karnak in size and complexity and better preserved in its entirety. It is also the only site in Egypt that has a well-preserved Pharaonic palace within its enclosure. Medinet Habu was both a complex of temples dating from the beginning of the New Kingdom (1569 BC) beforeRamses III enclosed both structures within a massive mud-brick enclosure that included storehouses, workshops, administrative offices, and residences of priests and officials. The complex’s massive enclosure walls sheltered the entire population of Thebes during the Libyan invasions of the 21st Dynasty (1081-711 BC) and for three centuries afterward it protected the Coptic population. The main attraction is the great memorial temple of Ramses III; it was a focus for the pharaoh’s cult, linking him to Amun-United-with-Eternity. The temple precinct measures about 214 m (700 ft.) by 305m (1000 ft.). It contains more than 22,350 m2 (75,350 sq ft) of decorated surfaces across its walls. You enter the site through the unique Syrian Gate, The Migdol Gate, which is named after the Syrian fortress that so impressed Ramses with its lofty gatehouse that he built one for his own temple. The front of the temple represented Ramses III in its relief as the victor in several wars. The most famous are the fine relief of his victory over the sea peoples and Libyans. Around the funerary temple, you will see the remains of an early Christian basilica as well as a small sacred lake. Some of the best reliefs are on the outer walls of the temple, the famous battle reliefs of Ramses II run along the temple’s northern wall, and they are in chronological order, as Ramses III intended them to be seen. Attached to the temple is one of the few King’s Houses that is still standing. The throne room and other spaces are well preserved, and visiting in the afternoon is the best time to see the detail of the colours and designs. The colour of many of its bas-reliefs is still intact, like the religious festivals and on the treasure chambers whose reliefs show the weighing of myrrh, gold, and lapis lazuli.

- Luxor museumThe excellent Luxor Museum was opened in 1975, and has a beautifully displayed collection of items from the end of the predynastic period right through to the Islamic era. Most of the items were gathered from the Theban temples and necropolis. A new wing was opened in 2004. The main reason for this wing is so that the royal mummies of Ahmose I and Ramses I could be displayed without their wrappings in dark rooms. Unlike the Egyptian museum in Cairo, Luxor Museum does not charge extra to see this wing. Further highlights of the museum are treasures from Tutankhamen and Akhenaton. A major exhibit is a reconstruction of one of the walls of Akhenaten’s temple at Karnak. One of the featured items in the collection is a calcite double statue of the crocodile god Sobek and the 18th Dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep III. A hall containing 16 statues that were uncovered in Luxor Temple in 1989, can also be viewed. All are magnificent examples of ancient Egyptian sculpture but pride of place is given to an almost pristine 2.45m tall quartzite statue of a muscular Amenhotep III. An extension called Thebes Glory focuses on the New Kingdom war machine that was honed against Egypt’s Hyksos invaders (1664-1569 BC) and later unleashed on neighbouring states. The ferry between the East and the West bank now stops right outside the Luxor museum.

- The Mummification museumThe Mummification Museum is the best place to learn about the most powerful secrets of the pharaohs. The museum opened in 1997 and was the first in the world to be dedicated to this subject. Though it isn’t large, each display is a story in itself, reflecting one of Ancient Egypt’s most important and famous traditions. Visitors are guided around beautifully displayed exhibits and story boards which explain the process of mummification from beginning to end, as well as the religious customs associated with burials. Vitrines show the tools and materials used in the mummification process, with several artefacts that were crucial to the mummy’s journey to the afterlife, as well as some strikingly painted coffins. There is also a mummy of an ancient high priest and a host of mummified animals on display, as well.

- Luxor marketShopping is a part of most holiday tours that people just can’t do without. Throughout the day and into the evening, you can look at the many shops in Luxor and find some souvenirs and great bargains to take home. The variety of products and smells is irresistible, from perfumes and incense to fruit and fish, as well as beautiful jewellery and material. Eye-catching piles of spices and dyes are heaped on the many stalls. make sure to take care of your wallet, as, even though it isn’t common, pickpocketing isn’t unheard of in Egypt.There are two main shopping areas in Luxor, both connected to each other. The first is the standard tourist bazaar: a long corridor filled with bright, colourful shops on both sides selling souvenirs of all kinds, including statues, silver and gold jewellery, T-shirts, dresses, Bedouin accessories, perfume, pottery, alabaster, oriental musical instruments, spices, leather goods, carpets, and papyrus. The prices, however, are often exaggerated and bargaining is essential. The second one is the ‘Oriental locals’ market, known as the old market (souk). It is not a tourist shopping area but a tour into Egyptian life. It has the authentic feel of a local market, and it is also a delightful and highly colourful market that attracts and enthrals every tourist. It consists of a very narrow street, where one mainly finds normal products that a local family might need, such as groceries, clothes, and household items, although there are many spice dealers as well, and some of the best peanuts you can find, in addition to the tourist souvenirs with the best prices. It’s a good place to meet local people and learn about the local culture. The smells, sounds, and sights will give you an excellent insight into Egyptian life. This tour is usually better by horse carriage.

- Ramsseum templeThe Rameseum in the Ancient Theban Necropolis, was built by Ramses II, not far from the Valley of the kings on the West Bank of Luxor, and in this fabulous mortuary temple, he identifies himself with the local form of Amun, the Sun-God. he also had a full depiction of Nefertari on one of the pylons Jean-François Champollion called it the Ramesseum. The building of the temple began early in Ramses’ reign and took around twenty years to complete, undoubtedly matching the great temple of Abu Simbel for monumental grandeur and self-glorification. It consists of two successive courtyards with pylon entrances, and a hypostyle hall with surrounding annexes. The first and second pylons measure more than 60m (197 ft) wide and feature reliefs of Ramses’ military exploits, particularly his battles against the Hittites. The Ramesseum is famous for the awesome fallen colossus of Ramses II, which stood at over 18m (60ft) tall and weighed about 1000 tons, meaning its size and weight are second to none but the Colossi of Memnon. The core of the Ramesseum is substantially intact, with an interesting set of reliefs on the ceiling, featuring the twelve-month calendar. The Great Hypostyle Hall had 48 columns, of which 29 are still standing and the colours are still fairly prominent. The whole complex is surrounded by mud-brick buildings that once covered about three times the area of the temple and included workshops, storerooms, and servants’ quarters, that have survived far better than the royal palace that once adjoined the temple, of which only stumps of walls and columns remain.

- Carter houseCarter House, an evocative museum dedicated to the British Egyptologist Howard Carter, is conspicuously situated on a low ridge overlooking the road to the Valley of the Kings. Carter lived here during his five-year search for Tutankamun’s tomb and its subsequent excavation. Simple to modern eyes, the mud-brick house features such Edwardian comforts as a gramophone and a kitchen with a bottled-gas stove, a spare bedroom for Carter’s patron Lord Carnarvon and his daughters, and a tiny photographer’s darkroom used for recording artifacts. You can see Carter’s shaving mug, sun-parasols, and the magnifying glass with which he pored over-excavation plans, seeking clues to the tomb’s whereabouts. An exact replica of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber has been constructed on the edge of the garden along with an exhibition relating to the discovery of the tomb. The replica has faithfully copied the shape of the original tomb, but only the burial chamber (right-hand side) has been reproduced here. The work is intended to challenge assumptions about our desire to see original objects and also to take some of the pressure off the original tomb. Although the young pharaoh’s mummy has not been included, every detail of the burial chamber has been exactly reproduced, including dust and pitting on the walls, the wooden railing, and cracks in the sarcophagus. The left-hand storeroom (not open in the original tomb) has been used to mount displays explaining how the tomb was discovered and reproduced. There is a cafe space on the side of Carter’s House which, when it reopens, will make this a peaceful place to stop for refreshment. The mud-brick building on the little hill above Carter’s house belonged to the French conservationist Alexandre Stoppelaëre. The Egyptian architect built the house for him in 1950. Empty for many years, it has now been restored as the base for the Theban Necropolis Preservation Initiative, a collaboration between the Factum Foundation for Digital Technology in Conservation in Madrid, the University of Basel, and the Ministry of Antiquities in Egypt.

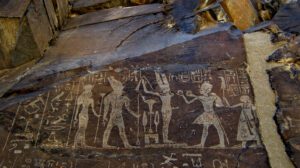

- Wadi HamamatWadi Hammamat is one of a great number of dry river beds that wind through the rugged mountains of Egypt’s the Eastern Desert. The rock art of the Eastern Desert is one of Egypt’s best-kept secrets, spread over 24,000 square kilometers (9,266) square miles. The route was used for millennia as a trade route from the Red Sea coast to the Nile Valley, but the area was also famed for its quarries and gold mines. This route through the mountains of the Eastern Desert was taken by travellers on their expeditions from the Old Kingdom onwards, right through to the Romans who exploited the quarries and gold mines the most, and who built stone watchtowers on the tops of the hills to guard the road and the wells. Scores of ancient ruins line the route; remains of watchtowers, forts, wells and mines from various periods show much evidence of ancient quarrying and mining activity. The wadi is perhaps best known, however, for its hundreds of hieroglyphic and hieratic rock inscriptions which record the activities of expeditions sent by many kings to obtain the precious resources of greywacke and schist-type rocks which were used for small-scale building projects, sarcophagi, statues and vessels during the Pharaonic Period. The colours of the rocks vary from a very dark basalt-like stone, through to reds, pinks and greens and although this stone was usually too flawed for building large monuments, they make a stunning backdrop in the valley. The valley is also famous for its ancient gold mines, one of them was active till recent times and the ancient workmen s village used to house hundreds or workers who mined stones and gold in the valley is still there. There is evidence in the area of prehistoric man (c.3500 BC), desert dwellers and nomads who left crude petro glyphs bruised into the rocks in the form of curved reed boats, hunters and long-gone animals, including elephants and ostriches, suggesting that the desert was at that time a more hospitable, lush place. On the southern side of the road, the cliffs are littered with inscriptions left by expedition members, many of which can be dated to the year of the reigning Pharaoh, providing invaluable historical records of the activities of a long line of kings. Wadi Hammamat was a Roman fort and major watering station for travellers through the wadi. The stone walls can still be seen, built to protect the well, 34m (112 ft.) deep, which had a winding staircase to the bottom. This is a great feat of Roman engineering and impresses on the visitor the vital importance of water in this arid landscape. The first European descriptions of the Wadi Hammamat were from the Scottish traveller James Bruce in 1769, though he made no mention of the inscriptions.

- Avenue of Sphinx WalkAvenue of Sphinxes or The King’s Festivities Road, also known as Rams Road (Arabic: طريق الكباش) is a 2.7 km (1.7 mi) long avenue , which connects Karnak Temple with Luxor Temple having been uncovered in the ancient city of Thebes (modern Luxor), with sphinxes and ram-headed statues lined up on both flanks. History Construction of the Avenue of Sphinxes began during the New Kingdom era and was completed during the Late period during the reign of 30th Dynasty ruler Nectanebo I (380-362 B.C.), the road was later buried under layers of sand over the centuries. In Description de l’Égypte (1809) the Avenue of Sphinxes is described as 2,000 meters long, lined with over 600 sphinxes. Georges Daressy reported in 1893 that at Luxor the road is buried and couldn’t be excavated because it lay below groundwater level, whereas at Karnak nearly a kilometer of it is visible. The first trace of the avenue (at Luxor) was found in 1949, when Egyptian archaeologist Mohammed Zakaria Ghoneim discovered eight statues near the Luxor Temple with 17 more statues uncovered from 1958 to 1961 and 55 unearthed from 1961 to 1964 all within a perimeter of 250 meters. From 1984 to 2000, the entire route of the walkway was finally determined, leaving it to excavators to uncover the road. The original 1,057 statues are along the way, and they are divided into three shapes:

- The first shape is a lion’s body with a ram’s head erected on an area of approximately 1,000 feet between the Karnak temple and the Precinct of Mut during the reign of the ruler of the New Kingdom Tutankhamun.

- The second shape is a full ram statue, built in a remote area during the eighteenth dynasty of Amenhotep III, before being transferred later to the Karnak complex.

- The third shape which makes up the largest part of the statue is a statue of the Sphinx (body of a lion and head of a human), the statues extend over a mile to Luxor Temple.